Press release 2019-05-06 at 10:51

A new assessment of levels of harmful substances in Finnish waters has been completed. According to monitoring activities, harmful levels of mercury, fire retardants and surface treatment agents are found in Finland’s aquatic environment. However, most of the substances being monitored do not constitute a hazard.

Sampling by Kymijoki. © Kuva: Alleco

Member States are required to monitor levels of 45 substances or substance groups in the aquatic environment. In the Water Framework Directive these substances are known as ‘priority substances’ and environmental quality standards have been set for their concentration in the surface water or biota. In 2013, eleven new substances were added to the list of priority substances, including several pesticides, dioxins and similar compounds, PFOS (used in surface agents and firefighting foams) and HBCDD (a fire retardant).

The Finnish Environment Institute (SYKE) headed a project funded by the Ministry of the Environment to measure levels of harmful substances in perch and mussels in coastal waters; in herring in the open sea; and in surface waters both at sea and in inland waterways. The burden on the environment from the new priority substances (e.g. fallout) was also assessed, and a plan was drawn up for future monitoring of harmful substances.

“This is the first time that we are getting a rough overview of environmental chemicalization in Finland’s waterways,” says the project coordinator, Researcher Katri Siimes from SYKE.

The findings lead to the conclusion that most of the new priority substances do not constitute a hazard to Finland’s aquatic environment. For instance, the fire retardant HBCDD does occur in waterways, but at levels considered harmless; moreover, most of the pesticides included in the list of priority substances were not detected at all. The levels of dioxins and similar PCB compounds also do not exceed the environmental quality threshold levels in the areas studied.

The environment is often more sensitive than people

Mercury and PBDE fire retardants remain the most problematic of the substances that have been monitored for a longer period.

Mercury levels in perch exceed the environmental quality threshold level (0.20–0.25 mg/kg) in about half of Finland’s inland waterways, but on the other hand, the maximum level defined by the EU for foods (0.5 mg/kg) is only exceeded very rarely. In herring in the open sea, mercury levels are now so low that there is no cause for concern. The fact that there is a different threshold value for mercury for environmental quality and for foods reflects the fact that ‘harmful to people’ and ‘harmful to the environment’ are two different things.

The environmental quality threshold value for polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE) is exceeded in fish everywhere in Finland, even though these fire retardants are no longer used at all. The situation is the same all over Europe. The environmental quality threshold value set for this substance group is extremely low (0.0085 µg/kg wet weight in fish), because there is very little toxicological data on its harmfulness and the safety factors applied are therefore considerable. No threshold value has been defined for PBDE compounds in foods.

Of the newly added priority substances, PFOS is of concern. PFOS has been used as a surface treatment agent and in firefighting foams. The use of PFOS has already been banned, but it continues to leach into the environment. PFAS compounds, which are very similar (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), are still widely used. Some of them were introduced specifically to replace the banned PFOS. PFOS levels in fish exceed the environmental quality threshold value in places (9.1 µg/kg wet weight). Various PFAS compounds were commonly detected in river waters all over the country. PFAS levels were the highest in Vantaanjoki river, and generally levels were higher in southern than in northern Finland.

Most pesticides constitute no hazard to the aquatic environment

More than 200 pesticides have been detected in Finland’s waterways, but most of them constitute no hazard to the aquatic environment.

DEET, used as an insect repellent e.g. in mosquito sprays is commonly found in the water but at levels that according to current knowledge are not harmful either to water life or to humans. Neonicotinoids, used as crop pesticides, were also found in the water.

New methods needed

New methods are needed for the monitoring of harmful substances, in terms of both sampling and impact assessment. For some substances, levels of significance for the environment do not even show up on measurements. Cypermethrin, for instance, is harmful even at lower levels than can be detected in water samples using current methods.

For substances that are present at extremely low levels or only occasionally, it would be feasible to use passive collectors sunk into the water for weeks, either in addition to or instead of water sampling. Passive collectors have proven to be a promising method for detecting pesticides and PAH compounds.

The environmental stress caused by harmful substances can be observed as biochemical and physiological changes in organisms, and these can be measured by analysing biomarkers. ”Research shows that biomarkers can yield a better overview than we have at present of the compound impact of various substances in the aquatic environment, even when the levels of individual substances remain under the threshold values,” says Head of Unit Kari Lehtonen from SYKE.

Proposal for future monitoring

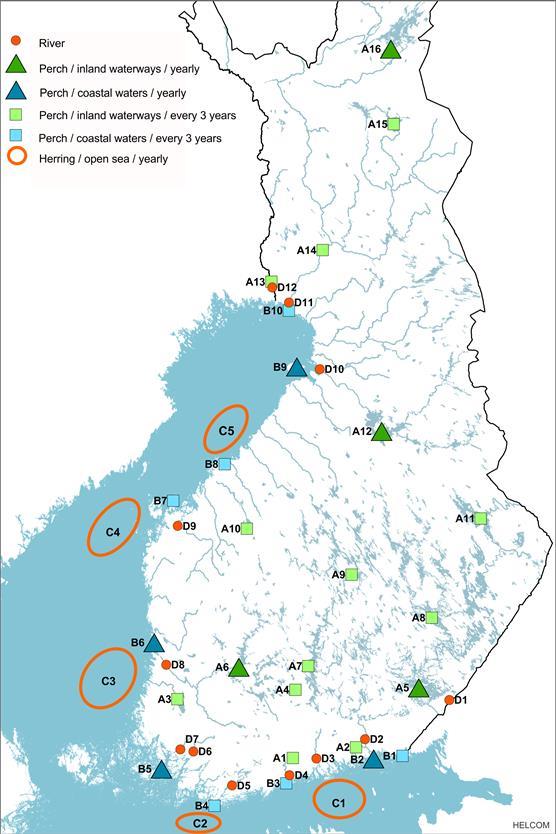

The project included drafting a proposal for future monitoring of harmful and hazardous substances. The proposal involves monitoring harmful and hazardous substances in the waters of 10 rivers flowing into the sea, in herring in the open sea at 5 locations, and in perch at 15 locations in inland waterways and 10 locations in coastal waters.

“It is essential for the effectiveness of bans and restrictions that we can make sure that the levels of banned substances in the environment are actually going down. Bioaccumulative and persistent substances are the most dangerous, and the most effective way of monitoring their levels is to analyse fish,” says Senior Scientist Jaakko Mannio from SYKE.

Proposal for future monitoring. © SYKE

Further information:

Project coordinator, Researcher Katri Siimes, Finnish Environment Institute, tel. +358 295 251 637, katri.siimes(at)ymparisto.fi

Senior Scientist Jaakko Mannio, Finnish Environment Institute, tel. +358 295 251 406, jaakko.mannio(at)ymparisto.fi

Head of Unit Kari Lehtonen (biomarkers), Finnish Environment Institute, tel. +358 295 251 359, kari.lehtonen(at)ymparisto.fi